Often described as the “Turkish Liberace” by media outlets, Zeki Müren was, and remains, an immensely important figure in the realm of Turkish popular music. Beyond his vocal gifts, however, Müren, for many, represents something deeper: both an icon of queer culture and a “model” Turkish citizen. In this brief presentation, I endeavor to bridge the gap between this two seemingly conflicting identities (among others in his life) and show how Müren could merge them both into one seamless performance, along with how his posthumous reception has shaped the way we discuss his work, along with the idea of Turkey as an often contradictory, yet modern society today.

I. Biographical Background

Müren was born to a somewhat wealthy tobacco and timber merchant in the city of Bursa, Turkey in December of 1931. Although Müren himself lists the year as 1933 in a 1965 poem, this claim has been refuted by most historians, and attributed to a matter of authorial vanity by Müren (Stokes 37). As a child, Müren possessed an affinity for music, but also pursued other talents, such as poetry and art (Purohit 2014). He spent a year at the Boğaziçi lycée, but eventually relocated to Istanbul to study music under Serif İçli and Refik Fersan, both affiliated with the Turkish Radio station. By the early 1950s, Müren found work regularly performing broadcasted concerts of Turkish art music, as well as soon delving into cinematic endeavors, thanks to a connection through his father’s work in the tobacco industry. He continued to star in a number of musical films, mostly playing loose versions of himself, until about the early seventies. Throughout this time period, he also found work in recording and performing at gazinos, nightclubs popular mainly among the Istanbul bourgeois. Eventually, Müren’s success began to somewhat slow as he faced a number of health issues, a decline in vocal ability, and a foray into the critically unfavorable arabesk genre in the 1980s. He retreated to Bordum for the remainder of his life and, in 1996, died as he had lived–onstage–his final words being: “I don’t know whether to laugh or cry.”

II. Film Work/Early Aesthetics

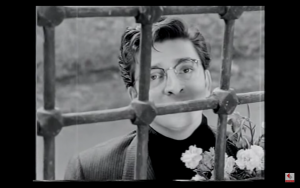

As earlier mentioned, Müren’s initial entry into the world of musical performance  took place through his performances on the Turkish Radio Station. From the very beginning of his career, his outstanding musicianship, attention to detail, and ability to perform under pressure was extremely apparent. For instance, his first broadcast in 1951, according to popular legend, as the broadcasts were not taped until at least the mid 50s, involved a maya improvisation to fill up nearly eight minutes of dead broadcast time. This particular program also featured particularly challenging repertoire and choice of makam (a concept akin to mode) which Müren handled flawlessly. He was also noted for his handling of diction throughout his career, using a very distinct pronunciation that some came to associate with the educated, urbane, Istanbul elite, and, from that vein, femininity. Yet, if Müren’s early vocal qualities hinted at the kind of campy performances that were to come, his film work bore no message of the sort. All of the films Müren starred in from the fifties to 1971, portrayed the same themes of the day, Müren as a serious, yet sensitive, artist, torn from one heterosexual love affair to another. These films also helped contribute to the popularity and circulation of his earlier recordings many of which where drawn from films, often composed by Müren himself, such as the below clip:

took place through his performances on the Turkish Radio Station. From the very beginning of his career, his outstanding musicianship, attention to detail, and ability to perform under pressure was extremely apparent. For instance, his first broadcast in 1951, according to popular legend, as the broadcasts were not taped until at least the mid 50s, involved a maya improvisation to fill up nearly eight minutes of dead broadcast time. This particular program also featured particularly challenging repertoire and choice of makam (a concept akin to mode) which Müren handled flawlessly. He was also noted for his handling of diction throughout his career, using a very distinct pronunciation that some came to associate with the educated, urbane, Istanbul elite, and, from that vein, femininity. Yet, if Müren’s early vocal qualities hinted at the kind of campy performances that were to come, his film work bore no message of the sort. All of the films Müren starred in from the fifties to 1971, portrayed the same themes of the day, Müren as a serious, yet sensitive, artist, torn from one heterosexual love affair to another. These films also helped contribute to the popularity and circulation of his earlier recordings many of which where drawn from films, often composed by Müren himself, such as the below clip:

His films also often featured religious iconography, such as the final scene from Son beste (The Last Musical Composition), from 1955, pictured below:

III. The Gazino and Performance

Müren supposedly had trousers and a miniskirt fashioned from the same fabric for this particular performance, and deliberated over his choice until the last moment, saying “What is important, my dear sir, is the reaction of the people. I would not disrespect that reaction” (Stokes, 45).

From about the mid 1950s to the early 1970s, Müren became extremely active in the gazino scene. Gazinos, at the time, were Turkish nightclubs, mostly frequented by the bourgeois educated and urban, which featured live musical performances, usually some variation on Turkish art and classical music, along with renditions of folk and popular tunes. Many of these establishments were extremely lavish, but also offered matinee performances for families who could not afford the type of relaxed consumption the bourgeois could (Beken). Müren’s performances became known for their lavish ornamentations, including a T-shaped stage, somewhat revolutionary use of the new cordless microphone as a prop, and the inclusion of a number of intricate costumes. In fact, Müren is credited by some with having brought the concept of wearing costume in gazino performances in Turkey, as illustrated by the below quote:

“At the end of the first rehearsal, I took them [the instrumentalists] to a corner told them this: Please, my masters, let us take a look at your costumes. As you know, I will wear three different costumes. A black tuxedo does not happen in summer concerts, but you could wear something like a blue jacket, gray pants and a gray bow tie, and accompany me like that. This has never been done in Turkey. I could bring this innovation with your assistance. Bless them, they listened to me patiently” (Gür 1996).

Müren’s style often blurred the lines of gender, featuring items such as miniskirts, and, as he aged, increasing amounts of heavy makeup and ornate jewelry. In fact, he even had a number of named costumes including “The tulip opening on the mountain peak” and “The snow mimosa” (Stokes 45). Yet, what set him apart from other artists of the time who also experimented with gender and performance, such as Bülent Ersoy, a transgender actress and singer of classical music, was his acknowledgement of religious and social traditions within the context of his performance. For instance, anecdotal evidence describes his cancellation of concerts due to religious adherence, and successful attempts at garnering a devout female audience through these and other respectful methods. In many ways, although Müren was outwardly extremely liberal in the context of performance, his personal life possessed values that likely lead to his framing as a “model citizen” by the Turkish populace before and after his death.

IV. Later Work, Death, and Construction of Legacy

Müren continued to release works throughout the 1980s until his death in 1996, most of which where critically unfavorable arabesk cassettes. Yet, even with this slight downfall and increasing questions regarding his sexuality posed by the media, his death in 1996 was marked by an elaborate state funeral, featuring at least 200,000 mourners in attendance. Following his death, however, the question of sexuality remained persistent. As Martin Stokes writes in his recent work The Republic of Love, the dialogue separated into two camps: those who attempted to uphold his status as heterosexual, fueled by the lack of his public acknowledgement, and perhaps the ideal of the platonic male relationships canonized in Sufism, and a second camp, those who claimed him as non-heterosexual, but disapproved of his failure to express this (Stokes 67). For instance, in her 2003 biography of Zeki, Emine Aşan proposes a theory of gender fluidity, in which Müren was able to maintain the different aspects of his gender identity through his personal life and performances. In many ways, this theory also seems to emulate the reasons why he may have been so easily claimed by the Turkish state after his death: his distinct separation between his private and personal self not only allowed people to cast aside his identity in consuming his music, but also echoed the state of Turkey which, in having a secular government, divided itself as well without clearly acknowledging the different parts. This sentiment still remains important to Turkey now, as it faces new conflicts such as the debate over whether it should enter the European Union, and what that means as its status as country that increasingly finds itself torn between belonging to both the East and West.

Müren continued to release works throughout the 1980s until his death in 1996, most of which where critically unfavorable arabesk cassettes. Yet, even with this slight downfall and increasing questions regarding his sexuality posed by the media, his death in 1996 was marked by an elaborate state funeral, featuring at least 200,000 mourners in attendance. Following his death, however, the question of sexuality remained persistent. As Martin Stokes writes in his recent work The Republic of Love, the dialogue separated into two camps: those who attempted to uphold his status as heterosexual, fueled by the lack of his public acknowledgement, and perhaps the ideal of the platonic male relationships canonized in Sufism, and a second camp, those who claimed him as non-heterosexual, but disapproved of his failure to express this (Stokes 67). For instance, in her 2003 biography of Zeki, Emine Aşan proposes a theory of gender fluidity, in which Müren was able to maintain the different aspects of his gender identity through his personal life and performances. In many ways, this theory also seems to emulate the reasons why he may have been so easily claimed by the Turkish state after his death: his distinct separation between his private and personal self not only allowed people to cast aside his identity in consuming his music, but also echoed the state of Turkey which, in having a secular government, divided itself as well without clearly acknowledging the different parts. This sentiment still remains important to Turkey now, as it faces new conflicts such as the debate over whether it should enter the European Union, and what that means as its status as country that increasingly finds itself torn between belonging to both the East and West.

V. Sources Cited