A question that consistently popped into my head while reading the Meintjes article was whether or not visibility trumped authenticity. There were multiple answers given within the article, but the one that stood out most prominently was on pages 55-56: “Simon ‘has filtered the [South African] sound with his own style, lyrics and Western influence to concoct a colorful collage which, while retaining its Afro elements, makes them less raw, more flowy, more gentle. And most pleasant.'” (Meintjes, 55-56). There’s a lot to unpack in this statement. By referring to South African musical traditions in this manner, the “filtering” of South African music is through a lens of palatability. Simon is extracting the “pleasant” bits of South African music in order to cater towards those that do not identify with this music tradition. I found this extremely problematic when applied to the section where Meintjes talks about white South Africans using Graceland as a portal into Black South African music culture. By using Graceland as the medium in which White South Africans entered into “their culture’s musical tradition”, this signifies that the interpreted version of Black South African music culture is what they identify with. Yet, as the article pointed out, many White South Africans would not have known that this musical tradition existed had it not been for Graceland. Which begs the question: was the visibility of Black South African music worth the inherent interpretation that had to occur for Graceland to exist?

Warning: Attempt to read property "comment_ID" on null in /home/theleahg/MusicPolitics20cEurope.theleahgoldman.com/wp-content/plugins/subscribe-to-comments/subscribe-to-comments.php on line 71

Warning: Attempt to read property "comment_author_email" on null in /home/theleahg/MusicPolitics20cEurope.theleahgoldman.com/wp-content/plugins/subscribe-to-comments/subscribe-to-comments.php on line 591

Warning: Attempt to read property "comment_post_ID" on null in /home/theleahg/MusicPolitics20cEurope.theleahgoldman.com/wp-content/plugins/subscribe-to-comments/subscribe-to-comments.php on line 592

Warning: Attempt to read property "comment_ID" on null in /home/theleahg/MusicPolitics20cEurope.theleahgoldman.com/wp-content/plugins/subscribe-to-comments/subscribe-to-comments.php on line 71

Warning: Attempt to read property "comment_author_email" on null in /home/theleahg/MusicPolitics20cEurope.theleahgoldman.com/wp-content/plugins/subscribe-to-comments/subscribe-to-comments.php on line 591

Warning: Attempt to read property "comment_post_ID" on null in /home/theleahg/MusicPolitics20cEurope.theleahgoldman.com/wp-content/plugins/subscribe-to-comments/subscribe-to-comments.php on line 592

Warning: Attempt to read property "comment_ID" on null in /home/theleahg/MusicPolitics20cEurope.theleahgoldman.com/wp-content/plugins/subscribe-to-comments/subscribe-to-comments.php on line 71

Warning: Attempt to read property "comment_author_email" on null in /home/theleahg/MusicPolitics20cEurope.theleahgoldman.com/wp-content/plugins/subscribe-to-comments/subscribe-to-comments.php on line 591

Warning: Attempt to read property "comment_post_ID" on null in /home/theleahg/MusicPolitics20cEurope.theleahgoldman.com/wp-content/plugins/subscribe-to-comments/subscribe-to-comments.php on line 592

Warning: Attempt to read property "comment_ID" on null in /home/theleahg/MusicPolitics20cEurope.theleahgoldman.com/wp-content/plugins/subscribe-to-comments/subscribe-to-comments.php on line 71

Warning: Attempt to read property "comment_author_email" on null in /home/theleahg/MusicPolitics20cEurope.theleahgoldman.com/wp-content/plugins/subscribe-to-comments/subscribe-to-comments.php on line 591

Warning: Attempt to read property "comment_post_ID" on null in /home/theleahg/MusicPolitics20cEurope.theleahgoldman.com/wp-content/plugins/subscribe-to-comments/subscribe-to-comments.php on line 592

Warning: Attempt to read property "comment_ID" on null in /home/theleahg/MusicPolitics20cEurope.theleahgoldman.com/wp-content/plugins/subscribe-to-comments/subscribe-to-comments.php on line 71

Warning: Attempt to read property "comment_author_email" on null in /home/theleahg/MusicPolitics20cEurope.theleahgoldman.com/wp-content/plugins/subscribe-to-comments/subscribe-to-comments.php on line 591

Warning: Attempt to read property "comment_post_ID" on null in /home/theleahg/MusicPolitics20cEurope.theleahgoldman.com/wp-content/plugins/subscribe-to-comments/subscribe-to-comments.php on line 592

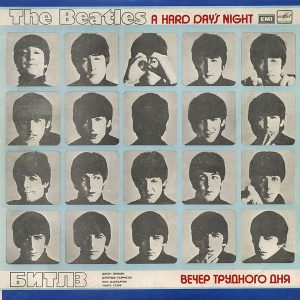

and other consumers of Western musical culture often “translated” the lyrics of popular foreign songs, by, as in the instance of future film actor Alexandr Abdulov and his friends, “inventing their own elaborate translations and stories for their [The Beatles] songs” (Yurchak 191). Yet, in most contexts, the meaning of the word “translation” accounts for a slightly different, perhaps more literal, product–rather, a “written or spoken rendering of the meaning of a word or text in another language” (Oxford English Dictionary 2016). To me, the “translation” described in Yurchak’s work seems to align more the idea of the x-ray disc, in that the newly created meaning of the text is overlaid over the content, rather than presented apart from it as a completely separate product. The result is a new cultural creation that owes to both Western and Soviet influences, such as Shagin’s “Beatles” piece, unlike pure translation which, arguably, simply puts the text and meaning of one language into another one.

and other consumers of Western musical culture often “translated” the lyrics of popular foreign songs, by, as in the instance of future film actor Alexandr Abdulov and his friends, “inventing their own elaborate translations and stories for their [The Beatles] songs” (Yurchak 191). Yet, in most contexts, the meaning of the word “translation” accounts for a slightly different, perhaps more literal, product–rather, a “written or spoken rendering of the meaning of a word or text in another language” (Oxford English Dictionary 2016). To me, the “translation” described in Yurchak’s work seems to align more the idea of the x-ray disc, in that the newly created meaning of the text is overlaid over the content, rather than presented apart from it as a completely separate product. The result is a new cultural creation that owes to both Western and Soviet influences, such as Shagin’s “Beatles” piece, unlike pure translation which, arguably, simply puts the text and meaning of one language into another one. Yurchak discusses that broadcasts in languages other than those spoken in the USSR were jammed (178) and as such the BBC World Service, amongst others, was readily available to Soviet music fans. How do we read this decision? To block broadcasts that were in Russian and the other languages of the Soviet Union suggests that the state saw broadcasts that were readily understood by the greater population as more dangerous than those that were harder to understand. This makes sense, sort of – a Russian language broadcast of Voice Of America, which could package an American agenda in a local language, was deemed more dangerous to Soviet society than an English language broadcast of the same station. Yet, Yurchak also makes clear that it was the “foreign sound,” “non-Soviet sound, and American English” (191) that listeners desired. Meanings did not matter; the broadcasts were valued by virtue of being foreign. By allowing these certain foreign language stations to be broadcast, those who did not speak or did not have the time and money to learn to speak foreign languages were excluded from the broadcasts. The “individualized practise of listening and doing it in a foreign language” (179) thus belonged to a privileged crowd. These circumstances seem to foster, rather than block, the production of so-called “bourgeois ‘art'” (185). It was, after all, groups like our dear friends the stiliagi who integrated American-English slang into their subcultural identity. How significant was the ability to speak in English (or other dominant Western language) as an exclusionary (bourgeois?) cultural signifier?

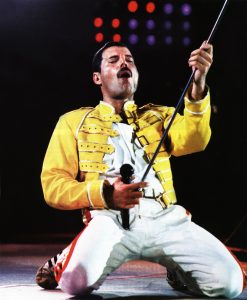

Yurchak discusses that broadcasts in languages other than those spoken in the USSR were jammed (178) and as such the BBC World Service, amongst others, was readily available to Soviet music fans. How do we read this decision? To block broadcasts that were in Russian and the other languages of the Soviet Union suggests that the state saw broadcasts that were readily understood by the greater population as more dangerous than those that were harder to understand. This makes sense, sort of – a Russian language broadcast of Voice Of America, which could package an American agenda in a local language, was deemed more dangerous to Soviet society than an English language broadcast of the same station. Yet, Yurchak also makes clear that it was the “foreign sound,” “non-Soviet sound, and American English” (191) that listeners desired. Meanings did not matter; the broadcasts were valued by virtue of being foreign. By allowing these certain foreign language stations to be broadcast, those who did not speak or did not have the time and money to learn to speak foreign languages were excluded from the broadcasts. The “individualized practise of listening and doing it in a foreign language” (179) thus belonged to a privileged crowd. These circumstances seem to foster, rather than block, the production of so-called “bourgeois ‘art'” (185). It was, after all, groups like our dear friends the stiliagi who integrated American-English slang into their subcultural identity. How significant was the ability to speak in English (or other dominant Western language) as an exclusionary (bourgeois?) cultural signifier? Whether or not audiences were tolerant of “glam rock’s play with gender,” glam was still seen as “provocative” (48) in the US and Britain – and deliberately so. This provocation was unequivocally political: Auslander notes that in the former, the “tendency to dress lavishly and use makeup” was seen to be a sign of “sexual abnormality” (49). I find it interesting that contrary to the criticisms of Ton Steine Scherben for not being ‘serious’ enough and using, for example, glitter in their performances, glam rock was political because of its lavishness and rejection of so-called seriousness. Unlike with Ton Steine Scherben, where showmanship and artistic personality were seen to dilute the band’s political nature, it was these elements that glam artists weaponised in their provocations of audiences/critics. I’m aware of the differing contexts (glam being commercial and Scherben being anarchist/’underground’, glam upsetting conservative audiences and Scherben frustrating left-wing ones), but it is nevertheless still interesting to see different aspects of an artist’s performance being read as political and the power of ‘lavish’ dress to agitate.

Whether or not audiences were tolerant of “glam rock’s play with gender,” glam was still seen as “provocative” (48) in the US and Britain – and deliberately so. This provocation was unequivocally political: Auslander notes that in the former, the “tendency to dress lavishly and use makeup” was seen to be a sign of “sexual abnormality” (49). I find it interesting that contrary to the criticisms of Ton Steine Scherben for not being ‘serious’ enough and using, for example, glitter in their performances, glam rock was political because of its lavishness and rejection of so-called seriousness. Unlike with Ton Steine Scherben, where showmanship and artistic personality were seen to dilute the band’s political nature, it was these elements that glam artists weaponised in their provocations of audiences/critics. I’m aware of the differing contexts (glam being commercial and Scherben being anarchist/’underground’, glam upsetting conservative audiences and Scherben frustrating left-wing ones), but it is nevertheless still interesting to see different aspects of an artist’s performance being read as political and the power of ‘lavish’ dress to agitate.