I. Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven was a German pianist and composer who lived from 17 December 1770 – 26 March 1827. (Grove Music Online) A student of Joseph Haydn, his compositions, his identity and his political legacy quickly propelled him to becoming inarguably one of the most famous and influential composers in Western Art Music. Due to his centrality in the Western Art Music canon, his role in musical life and history is to an extent international, bound to any culture which engages in classical music. However, his identity and political history as German, as well as Germany’s history of laying claim to Beethoven, complicate notions of the extra-locality of his work, his persona, and his legacy. Yet to an extent, his Germanness is often taken for granted, or naturalized, in the broader context of Western Art Music, which can be seen as perhaps coding the basis of the Western classical music tradition as German. To this end, what questions are raised about the impacts of his significance internationally when we consider Beethoven as emblematic, or formative of, a Germanness? What questions are raised about Germanness and Germany when we consider Beethoven’s legacy and impacts on a broad, international scale? In this blog, I will examine nodes of his legacy which rupture national lines (rendering him in some respects, ‘universal’), but ultimately also always implicitly index Germany and Germanness. I am interested in what his centrality in the Western Classical canon says about Germany’s place in relation to it, what political networks are engaged, and how these political networks function on an international scale. I’m driven by a question of authority: who owns Beethoven, how and when? When one deploys Beethoven, are they too deploying conceptions of Germany?

_________________________________________________________

, et al. “Beethoven, Ludwig van.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed October 10, 2016, , et al. “Beethoven, Ludwig van.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed October 10, 2016,

*Stock Photo – Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827). Piskarev, Nikolai Ivanovich (1892-1959). Woodcut. Modern. 1927. Private Collection. Graphic arts *Stock Photo – Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827). Piskarev, Nikolai Ivanovich (1892-1959). Woodcut. Modern. 1927. Private Collection. Graphic arts

______________________________________________________

II. Beethoven, Institutions and Germanness

As we have seen in our class’ readings thus far, Beethoven is one of the many canonical Western classical composers to have been claimed as emblematic of Germanness and Germany by German musicologists, propagandists and music critics prior to World War II. (Potter, 1998) While we have come to a consensus that there is no particular German essence to be found across all German music, the effort by musical and cultural “professionals” to cast a net which included Beethoven points to the effect of the phenomenon of musical museums described by Philip Bohlman in “The Music of European Nationalism,” in which music is institutionalized in museums, cultural bureaus and events in order to merge and mutually reinforce what Bohlman deems “myth and history,” and “nationalism and nation.” (Bohlman, 2004) In this sense we can consider the institutional treatment of Beethoven and his work in German history. I will engage with the Beethoven-Haus Bonn Museum, the museum founded in 1889 in his home in Bonn, which commemorates and maintains his work, his life, and his legacy, as a case study of this myth/history weaving.

The Beethoven-Haus Bonn Museum is “a historic memorial site (Beethoven’s birthplace), collection site, research centre and concert hall” in Bonn, Germany, commemorating Beethoven’s life, compositions, and legacies, and operated by the legal entity, the Beethoven-Haus Association. It receives half of its funds from public institutions (Eckhardt, 2008), and the rest through public fundraising. As a highly-visited, and long-running cultural destination, as well as an official heritage site funded on multiple levels by the German State, the museum is the historical epicentre of the modern Beethoven: the merging of mythic legacy and historical discourses which locate him physically within the nation of Germany, implicitly in discourses of German national identity, and explicitly in discourses of authority and authenticity in Western Art music. It appears that this location is a self-conscious, explicit choice on the part of the museum association, the Beethoven-Haus association. The institution directly claims that it, “The Beethoven-Haus[,] significantly contributes to the identity of the city of Bonn, known as Beethoven city,” in its multi-point mission statement posted on its website, situating Beethoven not just as an authoritative artist who continues to define the Western Art Music tradition, but as a major point of local German identity. Using Beethoven as a symbolic vessel, the museum explicitly links German identity to a legacy of artistic greatness, presenting itself both as a resource for those interested in his art, but also setting the terms of engagement to necessarily encompass local Bonn identity and by extension, German identity. Interestingly, their claim to Bonn as “Beethoven City” also implies a non-local, international gaze which reinforces this identity and their terms of engagement, placing Beethoven as Bonn, Bonn as German, and visitors as subject to these nested claims of identity.

The concept of the mutually reinforcing local, national and international identities through the iconizing of Ludwig van Beethoven can be considered through Bohlman’s lens of musical museums’ function, to productively consider cultural ownership and its necessary subtext, culturally-generated authenticity. If, as Bohlman writes, “the music of the museum revives the past and presents it to the present, celebrating the passage between myth and history and reinforcing the links between the nation and nationalism,” (Bohlman, 27) then we can better situate Beethoven in the broader function of the museum through examining Beethoven as a site of contestation over nation, authority, authenticity and ultimately, of ownership. If the museum explicitly states on their website that their mission is “to serve as a point of attraction and orientation and simultaneously have an influence on all segments of society,” through holding in reverence the work and life of Beethoven, how does Bohlman’s nationalism work in this context?

_________________________________________________________

Potter, Pamela, Attempts to define ‘Germanness’ in music, Most German of the arts: musicology and society from the Weimar Republic to the end of Hitler’s Reich , pp. 200-234, Yale University Press, 1998.

Bohlman, Philip, Music and nationalism: why do we love to hate them?, The Music of European Nationalism, pp. 1-34, ABC-CLIO, 2004.

Beethoven-Haus Bonn. “About Us.” Beethoven Digitally. http://www.beethoven-haus-bonn.de/sixcms/detail.php/58857.

Eckhardt, Andreas. The / Das / La Beethovenhaus Bonn. 2008, p. 13-14.

______________________________________________________

III. Beethoven in Outer Space

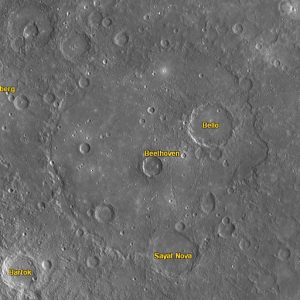

Over the past century, as man has ventured further and further into extraterrestrial terrains, new uses of Beethoven as symbol have come to the fore in ways that further speak to Bohlman’s concept of musical nationalism. One can look to Bonn, Germany, most music textbooks, or even childrens’ movies and see Beethoven, but equipped with the right telescope, one can also find him by looking up and out into the abyss of the galaxy. The Voyager Interstellar Mission, an ongoing American space program aimed at exploring interstellar space, included phonograph recordings of Earth music onboard, intended to showcase the best and most diverse terrestrial music to any extraterrestrial life or future humans. On the Voyager “Golden Record,” two pieces by Beethoven were included: Symphony No. 5, First Movement (performed by the Philharmonia Orchestra, conducted by Otto Klemperer) and String Quartet No. 13 in B flat, Opus 130, Cavatina (performed by Budapest String Quartet). The 1815 Beethoven, discovered in 1932 by Karl Wilhelm Reinmuth at the Heidelberg Observatory, is a main-belt asteroid between the orbits of Jupiter and Mars (the planets named after the King of the Gods and the God of War, respectively). The name references the first year of what musicologists often refer to as his “Late Period.” From 1815 until his death in 1827, Beethoven’s health and hearing deteriorated; his compositions bear the mark of his bodily and emotional state, heard through the emphasis on the low-strings of the orchestra, the highly intellectual and personally expressive nature of the music, his innovations in musical form. His iconicity can also be located in outer space at the Beethoven, a crater on the planet Mercury’s German quadrant.

Finding Beethoven in German-coded zones of outer space, and as representative of Earth on the whole, necessitates asking what power the action of naming holds, and what the legacy of a name can produce and reinforce. The action of naming essentially sets the terms of engagement in the object being named. As Germans have named parts of outer space after an iconic German historical figure, already terrestrially historically claimed as emblematic of Germany and Germnanness, they set engagement with these zones by choosing Beethoven to index the German nation, German history, and assert their preeminence in the canon of Western Art Music. Considered through Bohlman’s lens, in these instances, Germany is “employ[ing] music to “museumize” the nation-state, in other words, to preserve and present the very elements needed to realize nationalism through performance in the course of an ongoing history.” (27, Bohlman) The power of the name is thus not just a German self-referential positioning in the sake of nationalism, but a constantly emergent practice of performing, generating and reinforcing history for the international community.

_________________________________________________________

“Voyager – The Interstellar Mission.” NASA. http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/interstellar.html.

“Voyager Golden Record: Music From Earth.” NASA. http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/spacecraft/music.html.

Derekscope. “Mercury at Superior Solar Conjunction.” Derekscope. April 26, 2014. http://www.derekscope.co.uk/2014/04/mercury-at-superior-solar-conjunction/.

“1815 Beethoven (1932 CE1).” NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology: JPL Small-Body Database Browser. August 29, 2003. http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/sbdb.cgi?sstr=2001815.

“Asteroids – Overview.” NASA. http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/asteroids.

“Planetary Names: Crater, Craters: Beethoven on Mercury.” Planetary Names: Crater, Craters: Beethoven on Mercury. http://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/Feature/660.

IV. Beethoven and Rammstein: Beethovenian Composition and Neo-Industrial Pop

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qvvdo8rnaxk

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eU5xQpYQvYo

What makes a music, as a collection of sounds, sound German? Or rather, how does the history of nationalizing and institutionalizing Beethoven as German impact how one hears nationality in his, and other, music? Though there is no sound that is considered intrinsically German, what can we hear in Beethovian compositional styles and techniques, and how do we contextualize it? Further, through what means can we locate this enculturated aurality? Learning to what and how to hear in music, for many, often begins in institutional settings, like schools, or in popular media, like soundtracks in films or top 40 hits. In this vein, I would like to consider hearing Germanness as sonic enculturation through institutions and popular media.

Among many, many others, arguably the three most defining aspects of Beethoven’s compositional style are (1) his emphasis on the low string instruments in the orchestra and (2) the highly personally expressive, some could say dramatic, quality of his music (identifiable in his phrasing, and manipulative, playful harmony [particularly through unexpected methods of modulation]), and (3) “his creation of large, extended architectonic structures characterized by the extensive development of musical material, themes, and motifs.” (Beethoven.ws, 2007) When we hear Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, one can feel these three aspects, hearing them as characteristic of Beethovenian compositional style. Rammstein, a highly-prolific German pop neo-industrial band, have achieved enormous international success over the past decade as not only provocative, but as referential to a longer line of German musical greats such as Beethoven. (Littlejohn, 2013) Their international #1 hit, “Du Hast” not only shares the name of a Beethoven piece in The Ruins of Athens, Opus 113, but conveys the three identifying Beethovian elements.

These qualities in themselves cannot sound German, yet when we hear them in Beethoven’s music, we also necessarily interface with his position as a Great German Composer in discourse and history, through what we know of him through institutions, scholarship and media. In this sense, one’s ears become enculturated to hear Germanness in Beethoven, and Beethoven in Germanness. These stylistic points have less to do with a German essence, than with hearing Beethoven’s history in them, and thus hearing points of connection to other works bearing the same stylistic markers. If music museumizes the nation, reinforcing the synergy between history and myth through the performance of history, then hearing Beethoven automatically involves some level of indexing the sonic elements in the larger context of Beethoven the icon versus Beethoven in history, forcing one to engage with his place in the canon as German through the sound of his music. In this sense, can one identify other instances of hearing Germanness, through hearing other musics which employ similar low-register emphasis, dramaticism, and a sense of motivic development in an archetonic system?

“Beethoven.” BEETHOVEN : Musical Style and Innovations. 2007. http://www.beethoven.ws/musical_style_and_innovations.html.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GuW_T3RP1TE

In 1811, Beethoven wrote The Ruins of Athens, Opus 113, a collection of pieces written to accompany a play by the same name. The collection is a semi-programmatic venture which captures, on the one hand, stirs of Greek discontent under Ottoman rule and on the other, an ahistoric picture of pagan spiritual practice. Perhaps the most notable piece in the collection is the Turkish March, whose theme Beethoven references in other pieces of his, and whose orchestration heavily emphasises the Woodwind sections of the orchestra. The Ruins of Athens generally, and the Turkish March specifically, are politically significant in the context of the time period in Western Europe and Greece. Western Europe, in the 18th and 19th century, rediscovered Ancient Greece, amalgamating in a classicist wave that swept over the region with profound impact. Classicism, in sum, created the necessity for a reclamation and emulation of Ancient Greek arts, writings, and philosophy, culminating in a picture of Greece, created by Western European arts, scholarship, and political apparatuses, which was deeply dissonant with the reality of the impoverished, underdeveloped, provincial Greece which existed after several centuries of Ottoman rule. Germany, and in particular, German philosophers such as Winckelmann, Herder, and Baumgardten, who sought to create aesthetics as a subdiscipline of philosophy, came to be prominent figures in classicist thought. In combination with anti-Islamic sentiments deeply held by heads of State in the era and the imperialist impulses of many Western European nations at the time, the classicist and philhellenist philosophy Beethoven engaged with in The Ruins of Athens spurred a lively European interest in assisting Greece in their ongoing uprising for independence against the Ottoman Empire. Great Britain, Russia and France ultimately sent naval support to Greek revolutionary forces and with their help, the Ottoman Empire was overthrown, and a Bavarian prince was installed as Greece’s king. The German royalty of Greece endured until their ultimate violent expulsion by the Greek populace in the early 20th century. (Finlay, 1861)

The connection between Western arts, ideologies and political effect situates Beethoven’s Ruins of Athens within both (1) classicist and exoticising aesthetic interests in Western European Art Music at the time and (2) Western Europe’s examination of Greece as an insight into their own origin story and identity as European. As part of the greater movement of classicism at the time, music such as The Ruins of Athens was mobilized as a political, ideological power which resulted in the installation of German heads of State in Greece for almost a century. One way one can conceive of Beethoven’s Europeanness is through his implicit stylistic, ideological and therefore, political engagement in the broader context of European imperialism. Considered from the perspective of the classicist tradition as both an imperialist political mechanism and a yearning for a European origin story, how can one frame his figuration in German history in the following century by German musicologists, propagandists, and State cultural institutions? If we consider that the official anthem of the council of Europe and the European union is Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy,” the final movement of his 9th Symphony, how can one situate his canonicity in meaningfully both in German history and identity, and in European identity?