My project focuses on the songs of Siberian punk musician Yanka Dyagileva. Dyagileva navigated the gendered traditions of male bard culture and female poetic solemnity to produce music that spoke to the condition of womanhood in the Soviet Union. Dyagileva worked alongside a number of prominent male punk musicians during her career, thus creating a fanbase of her own. These collaborative projects harbored non-gendered political messages, aimed against the state as a whole, rather than internal politics of identity. Dyagileva’s solo work, by contrast, often spoke out against the systematic and violent abuse of women in Soviet culture and her personal struggles with mental illness. I hope to compare Dyagileva’s solo acoustic work to her Grazhdanskaya Oborona collaborations, examining how her stage presence and lyrical themes differed depending on her circumstance and audience. I also hope to explore how Dyagileva asserted herself within a masculine-dominated music scene, and how audiences responded to her work.

Yanka Dyagileva – Burn, Burn, Brightly (live performance)

Yanka Dyagileva – Home (live performance)

Yanka Dyagileva – My Sorrow Is Luminous

Alexander Bashlachev – Time of the Bells (live performance)

Live Performance with Grazhdanskaya Oborona

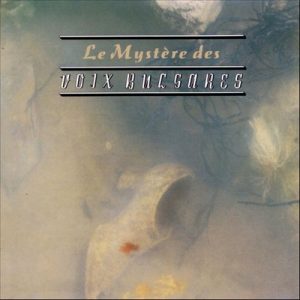

Furthermore, I find intriguing the position that the choir takes on a label roster such as that of 4AD’s. The marketing of the choir acts to assimilate it formally. To me, their music is aesthetically not dissimilar to that of label-mates Cocteau Twins, whose singer Elizabeth Fraser often referred to traditional Scottish song and even glossolalia in her vocal performances. Like the choir, Fraser’s vocal lines often deemphasized lyrics, instead employing melisma and trill (examples of Fraser’s vocals are

Furthermore, I find intriguing the position that the choir takes on a label roster such as that of 4AD’s. The marketing of the choir acts to assimilate it formally. To me, their music is aesthetically not dissimilar to that of label-mates Cocteau Twins, whose singer Elizabeth Fraser often referred to traditional Scottish song and even glossolalia in her vocal performances. Like the choir, Fraser’s vocal lines often deemphasized lyrics, instead employing melisma and trill (examples of Fraser’s vocals are